At the start of the second act of Trainspotting 2, Renton and Sick Boy, now more usually going by Mark and Simon but still played by Ewan McGregor and Jonny Lee Miller, enter an Orangemen‘s bar with the intention of leaving with as many credit cards as they can carry. They get eyed as the shady-looking sort, and for whatever reason have to prove themselves by getting on stage and singing a song. Renton sings a ballad of the Battle of the Boyne, a 1690 battle where the Protestants decisively defeated the Catholics, ending each stanza with “And all the Catholics left!” The bar, initially silenced, erupts into joyous applause, cheering and hollering for the removal of their Pope-loving historical enemies.

It’s a reasonably funny scene, but let’s unpack it a bit. Firstly, bringing the Orangemen into just about anything is just about the most Scottish thing ever. But Trainspotting 2 (stylized T2, as a big fuck you to Arnold I guess) uses this to bring up the power of nostalgia, and how long-festering grudges can be hard to squash. Throughout, Renton and Sick Boy talk about how good things were when they were young. Spud starts writing about their old days fondly. Begbie, fresh out of prison, tries to get his son to try his trade (burglary), a more honorable profession than what he’s in college for (hotel management). There’s more than a small echo of the “times have changed and left me behind” attitude that led to Brexit, but all it takes is a reminder of a dead friend and a dead child, or a quick shot of a particularly filthy bar toilet, to remind us that things weren’t really that great.

But where does that leave Trainspotting 2? Its on the fence about the power of nostalgia at the end of the day, but it itself is a product of nostalgia, something willed into existence by a handful of filmmakers and fandom of unknown size to bring back a time when movies were good, as if they’ve somehow flailed in the twenty years since. Plenty of archive footage of the original Trainspotting is present in the movie, along with frequency spliced footage of the characters as young children. Its willingness to confront this head-on and use it to examine its character’s psychology is admirable and occasionally poignant, and its certainly not a nostalgia product in the vein of, say, The Expendables. The return of the “Choose Life” monologue and its retweaking for the Internet era is hacky, but the lead-up to it, where Renton has to patiently explain why “Choose Life” was ever even relevant, says a lot about how nostalgia can leave you disconnected from the world you currently have to live in.

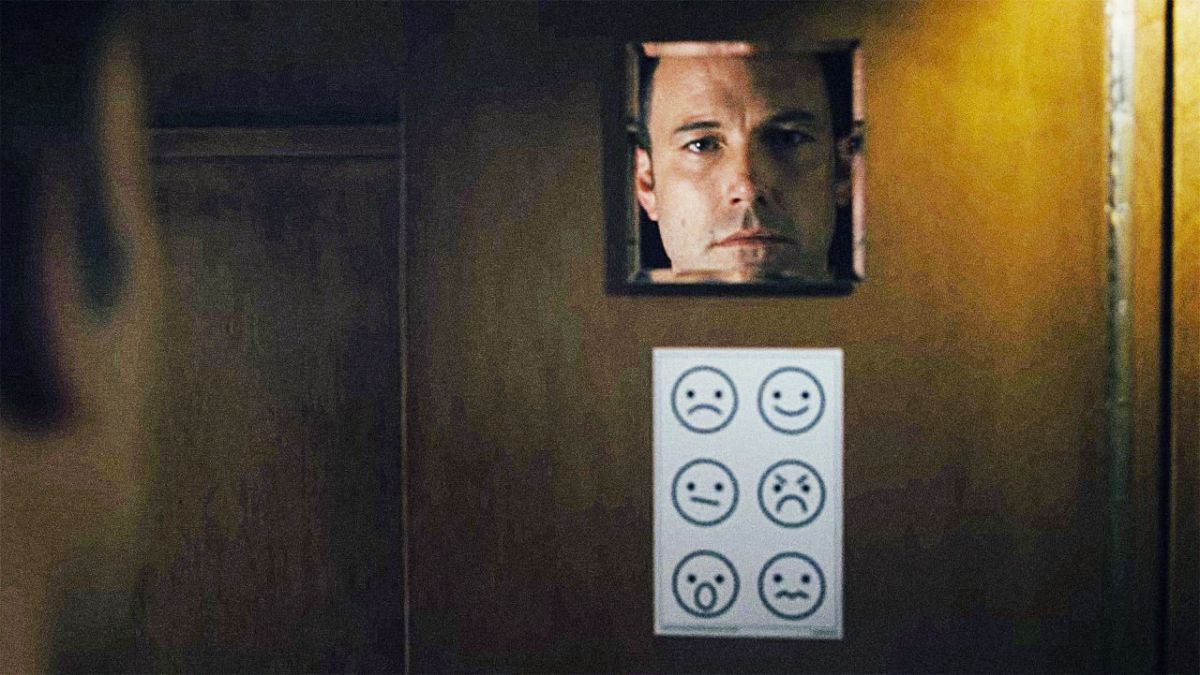

But while it explores some interesting thoughts, and Danny Boyle certainly puts together a few absolutely magnificent shots and setpieces (this being my favourite), he’s less interested in how the characters have changed over the years, and thus less interested in who they actually are now. Spud gets an honest-to-goodness arc, but it at times treats him a bit too much like an idiot savant. Without pre-existing knowledge about Renton, Sick Boy, and Begbie, there’d be no reason to really care about what happens to them over the course of the film. And the plot is a bit more defined than in the loose original, but its fairly unimaginative and lacks anything approaching the gut punches of the closing act of the original. Getting clean is always good, but it also means getting a bit dull in the Trainspotting world.

Veronica, a would-be madame and one of the few new characters in the film, is at one point asked why in the world she would want to go back to Bulgaria; it’s home, she replies, resonating with the somewhat-vague as to why Renton comes back to Edinburgh. It’s home, she says. There’s an emotional attachment. But if you don’t have an emotional attachment to Trainspotting to begin with, there’s not much T2 really offers.

C+

T2 Trainspotting (2017)

Directed by Danny Boyle

Starring Ewan McGregor, Jonny Lee Miller, Ewen Bremner, and Robert Carlyle

Rotten Tomatoes (75%)